Previsualization: Transforming Your Thoughts into Photos

Oh, they’re just a snapshooter!

That’s kind of the biggest slap in the face that you can give a photographer.

None of us want to believe that we’re snapshooters.

Truthfully, almost none of us are, because we all make decisions as we’re taking a picture—whether we realize it or not.

The picture above may appear to be a simple snapshot—a quick and meaningless moment captured.

However, it was quite the opposite. I conceived the photo and mentally prepared before the camera was even turned on.

There is a photographic term that encompasses this mental process of strategizing and executing an image: pre-visualization.

For a moment, imagine the term “pre-visualization” basically means “translation.”

With pre-visualization, you translate a three-dimensional scene, which you can see in real-life, onto a two-dimensional medium—a photograph. As you can imagine, a significant component of pre-visualization is composition.

The photo above is a perfect example. It was taken in Las Vegas from a 12th-floor hotel room. It depicts a cityscape that is partially obscured by a window shade.

What you see here is what I saw in my mind before clicking the shutter. I didn’t see a window shade or a cityscape; what I saw in my mind was a semi-abstract painting depicted in a photograph.

Key Thought: When attempting pre-visualization, imagine your scene printed huge, framed and hanging on a large blank wall. What do you see?

Pre-visualization began in Hollywood with moviemaking and the art of storyboarding.

Photographer Ansel Adams is credited with bringing the idea to still photography.

Pre-visualization is the art of seeing the finished photograph in your mind before you ever pick up a camera.

It may sound easy, but it requires developed skills in art knowledge, equipment, composition, lighting, exposure and post-processing.

The first step toward pre-visualization is training your eye to see the world in terms of spatial relationships, rather than literal objects.

A spatial relationship, in art, is the ability to perceive the involvement of an object’s position within a given space.

In this example photo above, I saw the pre-visualized the shape of a man in a dark suit surrounded by the space of white buildings.

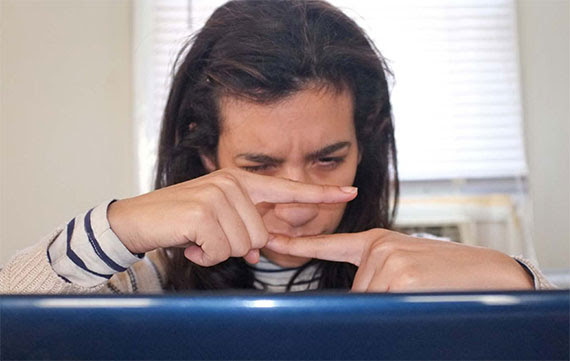

Idea: When I began taking photography seriously, a mentor of mine taught me this simple trick to help me develop my ability to see spatial relationships. Just cup your fingers and thumb to form a cylinder, then close one eye and hold the cylinder in front of the open eye

Viewing a scene that you wish to photograph through this “lens” removes your peripheral vision and gives you something closer to a two-dimensional perspective. In fact, if you watch documentaries on filmmaking, you will often see the filmmaker using this same technique.

It forces you to see your scene in terms of spatial relationships!

Critical Thought: Practicing spatial-relationship recognition is the first step in developing professional pre-visualization skills.

A spatial relationship is intrinsically tied to light, shadow, color, and shape.

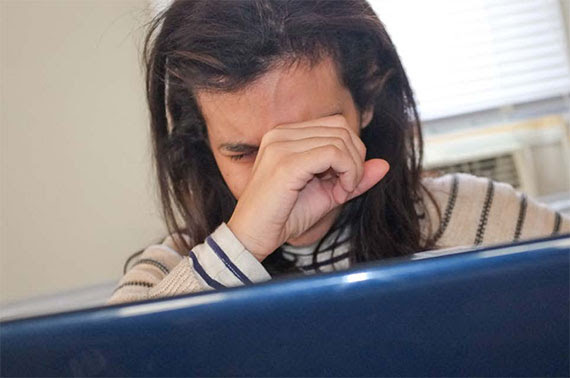

Another fantastic training tool for developing pre-visualization, similar to the technique above, is to view your scene through squinted eyes and using your fingers to “crop” the scene in front of you.

This activity eliminates details and divides the scene into spatial blocks of light, shadow, color and shape.

Idea: As you begin learning pre-visualization and using your eyes and hands as training tools, it’s best to stick with static subjects like landscapes. Once you’ve improved your pre-visualization to the point of no longer needing these techniques, you’re ready to take on moving scenes.

Key Thought: Moving scenes add an additional level of skill to pre-visualization. This extra skill is called anticipation.

This example photo is a perfect scene to begin pre-visualization practice:

Look at this picture using the techniques described above. You will see how it breaks down into a spatial relationship of shape, color, line and tone.

Critical Thought: Understanding your equipment is key to pre-visualization. If you don’t know how your equipment will affect the photograph, how can you pre-visualize it?

In my pre-visualization of the autumn tree photograph above, I saw an almost abstract image with blocks of color and a little to no perception of depth.

Knowing this, I selected a telephoto lens to compress the scene. That equipment further enhanced my preconceived idea for this photograph.

Critical Thought: Pre-visualization begins in the mind, advances to the camera and ends in post-production.

To take the photograph above, I physically saw an orange lawn chair that was sitting in a driveway in the late afternoon light. It was casting a shadow onto the concrete.

In my mind, I pre-visualized the scene as an abstract watercolor painting.

I physically created the picture by framing it as I saw in my mind’s eye, focusing on the shadow more than the chair.

I asked a friend to stand by the chair to cast a shadow in the upper left third of the frame. I felt this would further add a sense of mystery.

However—this is the crucial point in this illustration—this pre-visualized photograph came together in post-production.

Most of what you see in the final photo is nothing close to what was captured in the original digital file. Still, it perfectly completes what I preconceived as a painting on the wall!

In the moments before this photograph was taken, I thought, “Oh my god! She better watch out for those waves!” This thought was the formulation of my pre-visualized picture. But more was needed!

Other core skills for pre-visualization are patience, anticipation and timing.

In the example photo, part of my pre-visualization was to capture the danger and drama of the heavy waves crashing onto the beach.

Without the woman, the pre-visualized shot fails.

This picture was born of a pre-visualized concept. However, it also required patience for the idea to materialize naturally. I needed someone or something to enter the frame and provide a sense of drama and potential danger.

It also required anticipation (having my equipment ready) once the shot began to materialize.

Many people were walking in this area. Several of them got close to where this woman was but then backed away.

When I noticed her, I could see she was going to make a point of venturing out further than anyone else.

I anticipated her action and had my equipment ready.

Finally, I timed the shot for the best spatial relationship. As you can imagine, there was a lot of movement here. The woman did not linger out there on those rocks. I had to anticipate and react when both she and the waves were at their peak spatial relationship.

Key Concept: Think of pre-visualization in this order:

- Idea

- Spatial relationships

- Compose the frame in your mind

- Imagine the image large and hanging on the wall

- Introduce a story element

- Have your equipment ready

- Be patient for the story to develop

- Anticipate the moment

- Capture the shot at peak action

- Use post-processing to bring your award-winning photograph to life!

Why Don’t You Give It a Try?

- Organize a photoshoot where you will spend the better part of a day out taking pictures.

- Do not take a picture before spending at least five minutes thinking about the picture and anticipating what it would look like hanging on your wall. Set a timer.

- Post-process to your pre-visualized thoughts.

- Print a selection of your best efforts. Tape them to a blank wall in your home. Leave them there for a week.

- Each day, position yourself five feet in front of each photo and look at it for at least a minute, if not longer.

What Do You Think?

- Do your finished photographs reflect your initial pre-visualized intent?

- Were you able to follow through on your pre-visualization from beginning to end?

- Do you now have a basic understanding of how pre-visualization can advance your photography?